Book Review: Consciousness Explained

08 Feb 2020

Introduction

I have always been fascinated by what philosophers call the hard problem of consciousness. This refers to the problem of explaining how our subjective experience can arise from a physical system such as the brain. If the brain is ultimately a collection of atoms following the laws of physics, couldn’t it function perfectly well without there being anyone “at home”?

Over the years I’ve read many books on the subject, but none of them seemed to address this fundamental difficulty. On the one hand there were mathematically oriented books filled with many entertaining insights into the nature of recursion and abstraction but lacking content on actual human brains. On the other hand were the cognitive science and psychology books which investigated topics such as human behavior and language in great detail but, in my opinion, failed to provide a convincing account about why we ultimately feel anything.

I recently finished reading Consciousness Explained by Daniel Dennett and as a result, for the first time I feel as though I have made progress in understanding the hard problem. In my opinion, the defining feature of the book is that Dennett isolates a deeply held intuition many of us share which makes the “hard problem” so confusing. He then proceeds to weaken this intuition via careful examination of some of our common subjective experiences.

Contrary to the books title, I still have no idea how consciousness really works. But I now have a lot less trouble accepting that in principle it could be explained in terms of simpler components such as neurons or other biological machinery. It has slowly inched from the realm of eternal mystery towards that of a wonderfully complicated scientific problem.

In this post I will describe the key idea that I learned from the book, and show how it cleared up, or at least reduced, my confusion about the hard problem.

The Cartesian Theater

What Makes Consciousness So Confusing?

Suppose that there be a machine, the structure of which produces thinking, feeling, and perceiving; imagine this machine enlarged but preserving the same proportions, so that you could enter it as if it were a mill. This being supposed, you might visit its inside; but what would you observe there? Nothing but parts which push and move each other, and never anything that could explain perception. – Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

In this post I’m making the materialistic assumption that all aspects of the mind, including consciousness, can in principle be explained in terms of the physical laws governing the matter in our brains. In particular, I take the reductionist view that it is possible to create a conscious system out of simple unconscious building blocks. Indeed, the human brain is built out of electrons, protons and neutrons which are, to the best of our knowledge, completely described by quantum mechanics.

The notion of building complex systems out of simple building blocks is not new to us. It is amazing that we can build airplanes, but we do not worry about how it is possible to build a flying machine out of screws and bolts that can not fly on their own. We are all familiar with computer processors that can perform bafflingly complicated mathematical calculations which are built out of billions of simple transistors.

Perhaps more relevant is our understanding of life. We still do not understand life well enough to produce a living organism from scratch and there is still a debate as to how life should be defined. But there are no longer many vitalists arguing that there is some fundamental aspect of life that can never be explained in terms of the biochemistry of molecules such as DNA and proteins.

But when it comes to consciousness, it is hard to accept that it could ever emerge from the mindless interactions of simple components. And even when we do try to embrace that perspective, we end up getting tangled up in various paradoxes and never ending philosophical arguments. Why do the principles that we so readily apply to other unimaginably complex systems fail to satisfy us when applied to consciousness?

The reason, according to Dennett, is that our intimate familiarity with consciousness produces strong intuitions which directly contradict the reductionism described above. The paradoxes and confusion that we encounter while thinking about consciousness are the result of simultaneously entertaining mutually contradictory ideas. A major contribution of Consciousness Explained is to pinpoint the precise intuition that is at odds with reductionism. Once it is out in the open, we will proceed to investigate some of our common conscious experiences and demonstrate that this intuition is not as obvious as it appears.

The Cartesian Theater

Our intuitive models of the brain start with what appear to be peripheral components such as the retina, optical nerve, visual cortex, motor control and memory. We tacitly assume that these are channeled, or re-presented, through some type of central control center where thought and experience happen. In other words, we think that our brain mechanically processes inputs or execute outputs and that we only become aware of these phenomena when they pass through our “turnstile of consciousness”. Dennett calls the idea of a central control center Cartesian Materialism and refers to the control center itself as the Cartesian Theater. According to this theory, there exists a specific region deep in the brain where “it all comes together and consciousness happens”. For example, the theory claims that we are not aware of light entering our eyes until an image of our surroundings is presented to the Cartesian Theater.

This intuitive notion of consciousness is clearly at odds with reductionism and few people today would argue that it is literally true. For starters, there is the issue of infinite regress which comes up when you try to explain the Cartesian Theater itself. If the theater is simply composed of atoms then nothing is gained by assuming its existence. But if it cannot be explained in terms of simpler components then we must ultimately choose between the theater being either a single atom or some exotic form of matter than has never been detected, neither of which are particularly compelling.

Despite the Cartesian Theater’s logical flaws, it plays a major role in our intuitive understanding of the mind. As we will see later, our intuitive embrace of the theater is the foundation of many confusing paradoxes and thought experiments surrounding the study of consciousness.

The plan for the rest of this post in straightforward. We start by describing Dennett’s Multiple Drafts model which is his alternative to the Cartesian Theater. We will then revisit some of the more vexing paradoxes of consciousness. In each case, we will expose the Carteisan Theater as the underlying source of confusion, and show that a careful inspection of everyday experience favors the Multiple Drafts model, even at an intuitive level. Once this is accomplished, the clash between intuition and logic disappears and the force of the paradox is greatly diminished.

The Multiple Drafts Model

In this section we present Dennett’s alternative to the Cartesian Theater which he calls the Multiple Drafts model. The key idea is that the brain is composed of many smaller and domain specific subsystems, all operating in parallel and each performing a simple task. The subsystems are connected and constantly process incoming signals and generate outputs, resulting in a perpetual flux of mental activity which occasionally converges on a stable pattern. The “drafts” refer to the different interpretations of our sensory input that are constantly being promoted by our nervous subsystems.

At first glance the Multiple Drafts model is at odds with our intuitive understanding of the brain. It feels like our mind proceeds in an orderly progression starting by collecting inputs which are then presented to our internal “observer” and “thinker” which makes a judgment and ultimately executes a motor command. In contrast, the Multiple Drafts model disposes with the centralized command center and replaces it with a distributed collection of low level systems, each pursuing a simple objective until a broad consensus is ultimately reached.

In the sections that follow, the burden will be upon us to demonstrate that the Multiple Drafts model is a better description of our daily experience, even at an intuitive level. That being said, we will end this section with a simple, though perhaps contrived, example which highlights the difference between the two models.

The phi phenomenon (as seen on tv) is the apparent motion one observes when nearby signals alternate at high frequency. For example, consider the following image:

The blue circles in this image are just blinking in place with an offset of 150ms, but we observe a moving white dot which seems to exist even in the empty space between them.

Let us try to explain this with the Cartesian Theater model. According to that model, the change in color of each circle travels from the screen, to our eyes, through the optical nerve and ultimately is presented to the theater at which point we become conscious of it. But consider the state of the theater right after one of the dots turns white but while it’s neighbor is still blue. Since there is no reason to expect the neighbor to blink, why would the audience in the theater decide at that moment that there is a white dot moving between them?

One possible explanation is that the audience prudently reserves their judgment for at least 150ms until the neighboring dot has a chance to change color. This theory can be tested by asking subjects to press a button as soon as they see a specific dot change it’s color. It turns out that the response time minus the time it takes for signals to travel through the necessary nerves is significantly less than 150ms. In other words, there is not time for the theater audience to sit around and wait for the next dot to blink. One can wriggle out of this by all sorts of decidedly non intuitive theories of memory erasure and so on but our goal was never to use the phi phenomenon to logically disprove the Cartesian Theater - we’ve already seen that it logically contradicts our reductionism assumption. Rather, the point is to show that our intuitive embrace of the theater is not as intuitive as it seems.

They key issue with the Cartesian Theater in this example is that it imposes a strict order on the events entering our conscious experience based on the time it takes signals to reach a specific point in the brain. It implies a single instance in time in which a signal transitions from an unconscious signal originating from the eye to a conscious one as it passes the threshold of the theater. This is why attempts to explain experiences such as the phi phenomenon which involve non-linear (in time) reactions to sensory input are bound to get us in trouble.

On the other hand, the Multiple Drafts model easily handles the phi phenomenon without relying on explanatory contortions. According to this model, the change in the first dot generates multiple “drafts” of mental activity corresponding to a stationary dot, a moving dot and many other possibilities. The lack of supporting evidence for the non stationary drafts allows the stationary one to stabilize and ultimately trigger a button press. When the next dot blinks the suppressed moving draft takes over and this new dominant pattern of mental activity ultimately causes the person to say (out loud or to themselves) that they saw a moving dot.

In the remaining chapters we will build our intuition for the Multiple Drafts model by inspecting some common everyday experiences. In the process of doing so we will shed light on some of the paradoxes and mysteries which typically occur in the study of consciousness.

Do We Mean What We Say?

In this section we address the following problem: Suppose you make a machine that can pass the Turing test. It can take inputs in the form of character strings and produce responses that are indistinguishable from those of a person. But the machine is clearly just mindlessly shuffling bytes without there being “anyone home”. Surely this is not the same thing as a conscious person talking since we mean what we say. How could a reductionist theory of consciousness ever explain the fact that we, unlike computers, mean what we say?

Let’s try and lay out the assumptions behind this argument. Our intuitive model of speech production posits a clean sequence of steps. First we decide our intent, or in other words, we decide what we want to say at an abstract level. This intent gets passed to a language specific system which generates words. These get passed to a grammatical module which fits the words into a sentence. Finally, this sentence gets passed to the speech production system which executes a pattern of breathing and vocal cord movement.

It’s possible that your intuitive model is somewhat different, but the key idea is that there is a special system that initially determines what we want to say, and that this kicks off the rest of the speech synthesis process. This high level coordinator is another word for Dennett’s Cartesian Theater. The reason the problem of intent and meaning is so confusing it that it is based on the intuitive Cartesian Theater which is indeed logically incompatible with reductionism.

Before debating this any further it makes sense to take a step back and ask “Is this intuitive model correct?”. Dennett claims that the answer is no. And indeed you can verify this by asking yourself a simple question: When you engage in normal conversation, do you usually know what you are going to say?

I admit that I initially found this suggestion preposterous - of course I do! But after observing myself during social interactions I realized that indeed words just sort of appear on my tongue and seem to be influenced mainly by previous words and elements of my environment such as other people’s words. Most people I’ve asked about this report the same thing. The exceptions were a few people, perhaps more filtered than myself, who told me that they sound out words in their head before saying them. But this just kicks back the question up a level - they agreed that they did not know what words would appear in their heads before sounding them out. Indeed, what would be the point of talking to yourself if you already knew what you were going to say?

The takeaway is that when we really think about it, our experience does not obviously point to a top down chain of command where our abstract thoughts are systematically converted into utterances. Rather, certain aspects of our experience are consistent with a chaotic marketplace of neural subsystems constantly forming and reforming coalitions.

We can find further evidence for this perspective by considering exceptions to the typical process of speech generation.

Sometimes a person will say something for no particular reason other than the fact that they like the way it sounds. For example, ever since I started watching Brooklyn 99 I find myself reacting to many situations with Jake Peralta’s patented catchphrase “Noice”, even when the underlying meaning of “nice” is not strictly warranted. On a more cynical note, a few weeks ago I asked a receptionist how much longer it would take to be seated and when they answered “15 minutes” I immediately said to myself “can save you 15% or more on car insurance”. These phenomena fit the Multiple Drafts hypothesis quite well. There are multiple subsystems in our brain trying to trigger a system wide response and sometimes the sillier “drafts” end up winning control.

A more extreme and unfortunate example is a condition called jargon aphasia. People with this condition frequently make nonsensical word choices, sometimes uttering completely incomprehensible sentences, despite performing well on other measures of intelligence. It appears as though they produce speech without any high level directive.

Many of the principles that apply to speech also hold for our internal monologue. It too does not follow a strict top down policy and can frequently be influenced by common templates and word patterns that we pick up from others. This is at least the way it feels to me when, for example, I talk myself through the steps of a well known procedure.

In summary, our difficulty with believing that a machine could reproduce all aspects of human speech is based on an intuition that speech is initiated from a single source of meaning and intent - the Cartesian Theater. This intuition is not compatible with a piece of machinery that can be reduced to simple components, each devoid of meaning. Our approach to resolving this conflict is to challenge the Carteisan Theater by providing intuitive support for the Multiple Drafts model.

Awareness

A key aspect of our conscious experience is that we do not just mechanically react to sensory inputs. There is clearly a distinction between reflexive actions such as recoiling from a hot object and deliberate activities like drawing a picture or solving a math problem. The latter seem to involve an inner observer or witness to the proceedings. How could a computer ever perform a deliberate action? Isn’t anything a machine does reflexive by definition?

It may not surprise you to hear that this question is also rooted in a profound intuition for the Cartesian Theater. Indeed, our intuition is that reflexes exploit hard coded circuits connecting sensory inputs to motor control but deliberate actions require these inputs to pass through the “turnstile of consciousness” so that the audience in the Cartesian Theater may devise an appropriate response.

In this section we will analyze these two fundamental types of actions and see that the difference is not as clear as it may seem. As usual, the goal is not to provide a logical proof of anything, but rather to weaken our intuition for the Cartesian Theater just enough so that we can begin to entertain alternatives such as the Multiple Drafts model.

The Unconscious / Conscious Boundary

One strong source of intuition for the Cartesian Theater lies in the apparent distinction between conscious and unconscious actions. An example of this distinction is the phenomenon of an object “hiding in plain sight”. It is possible for us to look directly at an object such that the light reflecting from it passes into our eyes and down our optical nerve but still not be conscious of it. At some point something happens and the object passes across some sort of boundary into the realm of consciousness.

We can study this boundary by noting that awareness seems to be necessary for following instructions. Consider the following command: “Raise your right hand if you unconsciously observe a blue square”. It would appear as though this command makes no sense. How could you decide to raise your hand without being consciously aware of the square? However, it is actually possible to fulfill this strange request. All you have to do is practice by sitting in front a computer flashing various shapes and raising your hand when you see a blue square. Over time you will get better and better at this until you can raise your hand in response to the square before you even know what’s happening.

This example seems contrived, but far from being the exception it seems to be the rule. Learning a new skill involves a gradual transition from the realm of conscious deliberations to reflexive and automatic reactions. This phenomenon is evident in physical activities such as playing a piano or shooting a basketball but it is also a key feature of learning mental skills. For example, when we learn multiplication tables in school we eventually get to stage where the phrase “3 times 7” causes us to reflexively respond with “21” - either out loud or to ourselves.

Here is another example which may be of practical interest to undergraduate students. Exams in large entry level mathematics classes are typically graded by assigning each question to a different graduate student. Each grad student will grade hundreds of responses to their question over the course of a few hours. In my experience, which has been confirmed by some of my friends, the grading process starts slowly as care must be taken to find the spot on the page containing the answer and verify the student’s reasoning. However, after looking through around 100 exams I sort of “get in the zone” and can predict a student’s grade after staring at their worksheet for about two seconds.

We have seen some examples where a conscious activity can slowly turn into an unconscious one. The converse is possible as well. For example, we can train ourselves to become aware of certain sounds and tastes that we currently ignore. A big source of examples is learning a foreign language. If you immerse yourself in a foreign country the language will initially sound like an indistinguishable stream of sounds. Simply learning a single word of the language will cause you to start hearing it everywhere. The same goes for learning to recognize subtle pronunciation differences.

As another example, we can learn to recognize flavors in foods like wine, beer, chocolate and coffee. With practice we can become aware of flavors that we otherwise would not have know existed.

In summary, many aspects of our learning experience are not easy to reconcile with the strict turnstile of consciousness imposed by the Cartesian Theater. How about the Multiple Drafts model? In this model, we become aware of sensory input if that input triggers a self sustaining pattern of mental activity. The strength and duration of the pattern determines our awareness level. When we learn a new skill, we create connections and frameworks in the brain that make it easier for certain patterns to persist.

The Mind’s Eye

One strong source of intuition for an internal observer is the phenomenon of the mind’s eye. To be concrete, consider the following mental rotation question [Shepard (1971)]1. Are two figures below the same except for their orientation?

As you attempt to solve these sorts of puzzles, it may feel like you are rotating the shapes in your mind’s eye. This intuition is supported by the fact that the time it takes to answer these type of questions has been shown to be linear in the degrees of rotation that are required. This seems to be good news for the Cartesian Theater - we solve mental rotation problems by projecting a rotating version of the reference shape in the theater and waiting until it looks the same as the comparison shape.

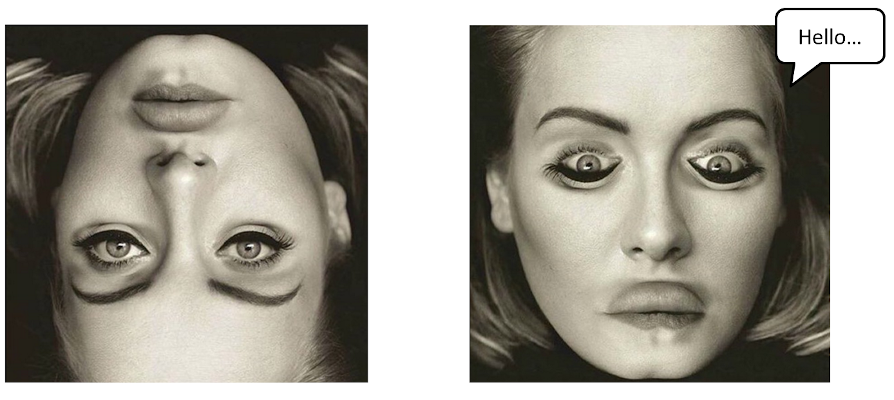

Things start to get interesting when we consider simple variations of this experiment. Perhaps the most famous is the Thatcher Effect where our random assortment of blocks is replaced with a human face. The result is that local changes to the face are significantly harder to detect when the face is turned upside-down. Here is an example with Adele:

In this example, Adele’s eyes and mouth have locally been flipped upside-down. This is obvious, and quite disturbing, when we look at the image on the right, but less so for the rotated version on the left. If we truly possessed the ability to rotate images in our mind’s eye, shouldn’t we be able to mentally rotate the image on the left by 180 degrees and experience the same reaction that we do to the one on the right?

Another interesting line of research studies the relationship between the object’s familiarity and the mental rotation speed. In general, we rotate familiar objects significantly faster than arbitrary ones. E.g, we can rotate letters of the alphabet more quickly than random squiggles. A cool demonstration of this was given by Sayeki (1981) 2 who showed that even providing the subject with a familiar interpretation of an abstract shape reduced the time they needed to solve a mental rotation problem by as much as 2 seconds! For example, in the case of the block image above they told subjects to imagine that the left image represented a person sitting on a chair and sticking out their left arm.

One takeaway from these results is that solving mental rotation problems is not a simple matter of turning a literal picture around in our head. Rather, it appears as though we are also interacting with abstract mental structures (such as a face or chair) that we associate with the reference image. As usual, this is not irreconcilable with the Cartesian Theater but clearly our initial intuitions do not tell the full story.

Qualia

The philosophical notion of qualia frequently comes up in the context of understanding consciousness. The idea is that objects in the world seem to possess certain subjective qualities which can not be explained in terms of their physical attributes. A common example is the quality of the color red. Consider this beautiful red square:

Proponents of qualia would note that even if you perfectly describe the wavelength of the light coming off the screen, the electrochemical reactions it triggers in your retina and the neural activity induced in your brain, there is still some essential redness which has not been explained. Since this redness is clearly part of our consciousness, doesn’t this mean that physical explanations of consciousness are doomed to failure?

Due to the fact that the very definition of qualia is debated by philosophers, in this section we will focus on a famous thought experiment proposed by Frank Jackson 3 which goes as follows:

Mary the color scientist knows all the physical facts about color, including every physical fact about the experience of color in other people, from the behavior a particular color is likely to elicit to the specific sequence of neurological firings that register that a color has been seen. However, she has been confined from birth to a room that is black and white, and is only allowed to observe the outside world through a black and white monitor. When she is allowed to leave the room, it must be admitted that she learns something about the color red the first time she sees it — specifically, she learns what it is like to see that color.

The takeaway is that there is a subjective aspect to color that can not be captured by physical facts. The only way to know what it feels like to see color is to actually see it. We can all imagine Mary seeing a red rose for the first time and exclaiming “So that’s what red looks like!”.

In this case we will confront the issue directly rather than following our usual program of tracing it back to a lingering belief in the Cartesian Theater.

According to Dennett, the fundamental problem with this thought experiment is that we take it for granted that even after knowing every physical fact about color, Mary will still be surprised when she steps outside of the room and sees red for the first time. In Dennett’s words, we are “mistaking a failure of imagination for an insight into necessity.”

He claims that we are greatly under-estimating what it would take to really know everything about the color red. As a first approximation, maybe this involves knowing that the wavelength of red light is about 680nm and that this light triggers a specific set of cells in our eyes. Everyone agrees that if all Mary knew was a perhaps embellished version of this description then upon actually seeing red she would be quite surprised indeed.

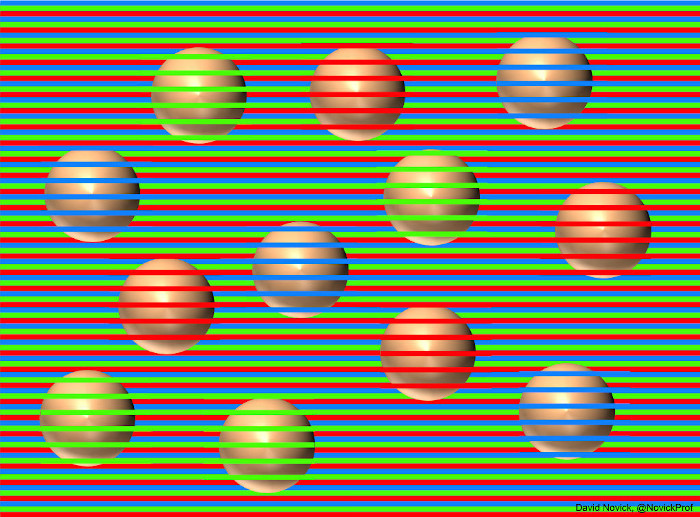

But what really is color? It is now well known that our color perception of an object is influenced by many factors including, but not restricted to, the wavelength of light it reflects. As a cool illustration of this, consider the following image:

It may surprise you to hear that all of the balls in the image have exactly the same RGB values. You can verify this by covering up the lines (the source contains an animation of the lines being added and removed) or zooming in until the lines become far apart. From this example we learn that the color we associate with an object is influenced by its environment.

Another demonstration of the precarious relationship between color and wavelength is the absence of a wavelength corresponding to the color brown. Look at a rainbow and note that there is no brown to be seen! There is clearly some visual property shared by chocolate, chipmunks and violins but wavelength alone can not describe it. I’d recommend checking out this video if you want to learn more about brown.

Finally, phenomena such as The Dress show that even people with perfectly healthy retinas may not be able to agree on what colors appear in a given picture. In fact, even an individual may experience color differently depending on the season of the year! 4

From these sorts of examples we conclude that it is not possible to define color in the abstract without referring to the specific human brain that is observing the world. A complete description of the color red only makes sense in the context of a single person at a particular point in time, and involves specifying a precise mental pattern that is triggered by various objects and images.

What does all of this mean for Mary? Well, in the process of learning everything there is to know about the color red she must have discovered the exact pattern of mental activity that firetrucks and roses would trigger in her brain. She could use this knowledge to create a machine that would stimulate her brain in that precise fashion. Having done so, it is reasonable to expect that she would not experience anything new when she steps out of the room.

You may object that creating a machine brain interface is not allowed. But why should be Mary’s brain modification technology be restricted to old fashioned tools such as words and diagrams? It is possible that language is simply not rich enough to convey something as subtle as redness. Even with this restriction, it is also possible that a person with Mary’s capabilities could devise a clever string of words that would unlock the desired neurological response.

Philosophical Zombies

A philosophical zombie is a being which behaves exactly like a human but has no subjective experience. It is easy to imagine such an entity. For example, maybe it is a robot controlled by a massive array of GPUs running the latest and greatest machine learning algorithms. On the outside it would engage in typical human activities such as watching Netflix and tweeting stuff. But on the inside it would be cold and dark - just electric impulses shuffling through wires without anyone “at home”.

The existence of such a zombie seems plausible, but doesn’t this imply that no physical description of the brain could ever bridge the gap between a mindless zombie and a conscious human being?

Dennett’s answer to this question is simple: No, philosophical zombies are not possible.

One of the reasons we think we can imagine them is our stubborn intuition for the Cartesian Theater. Following this intuition, one makes a zombie by replicating all of the machinery in the brain except for that special area containing the theater.

But as we have seen, such a theater is logically inconsistent with reductionism. Furthermore, even the theater’s intuitive appeal is diminished after careful inspection of some common subjective experiences.

Another reason for the seductive nature of the zombie argument is that we greatly oversimplify what it would take to build one. For example, it must be possible for you to collaborate with this zombie on a complex project for many years without you noticing that anything is off. Such a machine would be significantly more advanced than anything we could build today and it is premature to assume that we know anything about it at all. We certainly are not in a position to speculate about the nature of its consciousness.

Conclusion

I hope I have been successful at explaining why Dennett has changed the way I think about consciousness. The key realization was that the philosophical knots I used to tie myself in while thinking about the subject could be traced to my simultaneous belief in reductionism and intuition for the Cartesian Theater.

The next step was to consider a possible alternative to the theater such as the Multiple Drafts model.

Then came the real work of shifting my intuition from the pernicious Cartesian Theater to this new model. This was done by carefully inspecting key aspects of consciousness such as speech, thought and awareness which defy simple theater theoretic interpretations.

To conclude, here is a quote from the book in which Dennett provides a “thumbnail sketch” of his theory:

There is no single, definitive “stream of consciousness,” because there is no central Headquarters, no Cartesian Theater where “it all comes together” for the perusal of a Central Meaner. Instead of such a single stream (however wide), there are multiple channels in which specialist circuits try, in parallel pandemoniums, to do their various things, creating Multiple Drafts as they go. Most of these fragmentary drafts of “narrative” play short-lived roles in the modulation of current activity but some get promoted to further functional roles, in swift succession, by the activity of a virtual machine in the brain. The seriality of this machine (its “von Neumannesque” character) is not a “hard-wired” design feature, but rather the upshot of a succession of coalitions of these specialists.

The basic specialists are part of our animal heritage. They were not developed to perform peculiarly human actions, such as reading and writing, but ducking, predator-avoiding, face-recognizing, grasping, throwing, berry-picking, and other essential tasks. They are often opportunistically enlisted in new roles, for which their native talents more or less suit them. The result is not bedlam only because the trends that are imposed on all this activity are themselves the product of design. Some of this design is innate, and is shared with other animals. But it is augmented, and sometimes even overwhelmed in importance, by microhabits of thought that are developed in the individual, partly idiosyncratic results of self-exploration and partly the predesigned gifts of culture. Thousands of memes, mostly borne by language, but also by wordless “images” and other data structures, take up residence in an individual brain, shaping its tendencies and thereby turning it into a mind.

-

Shepard, Roger N., and Jacqueline Metzler. “Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects.” Science 171.3972 (1971): 701-703. ↩

-

Sayeki Y (1981) “Body analogy” and the cognition of rotated figures. The Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition ↩

-

Jackson, Frank (1982). “Epiphenomenal Qualia”. The Philosophical Quarterly. 32 (127): 127–136 ↩

-

Welbourne, Lauren E., Antony B. Morland, and Alex R. Wade. “Human colour perception changes between seasons.” Current Biology 25.15 (2015): R646-R647. ↩

Comments

The comments are powered by the utterences Github app. If you do not want the app to post on your behalf, you can comment directly on this Github issue.